High Rise Life

The Shard, at 306 metres the tallest building in the EU, nestles into the crook of the River Thames and London Bridge Street. It's postcode is SE1 and therefore forms part of the South East London city-scape, technically. Located in the London Borough of Lambeth, it looks north, across the river towards the City. It's glass cladding echoing the rash of new skyscrapers, a beacon to those smaller homes of banks and insurance firms. It is as if it turns its back on its stumpier, more utilitarian brothers and sisters, the real high-rises of South East London huddled around the Elephant and Castle roundabout, such as The Strata, Guy's Hospital Tower Wing and the current and former estates at the Aylesbury and Heygate.

The Strata (148 metres), variously called the Lipstick or the Razor, was completed in 2010 at the Elephant and Castle, a 43-storey residential building designed to be self-sufficient with wind turbines built into the roof and rain-water recycling facilities. It's only two years older than The Shard but seems much older already attracting some criticism that its eco-credentials may not be holding up with persistent rumours that the roof mounted wind-turbines are prevented from turning by noise complaints from upper level residents.

Its split of housing-association, right to buy, private flats and penthouses can be seen as a microcosm of London; social housing butting up against multimillion pound high-rise living. In many ways it is the modern heir to 1960s optimism in vertical living – diverse communities living upwards, private homes mixing with shared spaces. This optimism continues as The Strata is one of the few recent mixed towers to not have the distastefully media-dubbed ‘poor doors’ – separate entrances for social housing and less well-off tenants.

It currently overlooks the building site that once was the Heygate Estate. Designed by Tim Tinker in the early 1970s under the influence of Le Corbusier it was meant to be a beacon of optimism after the inner-London housing issues caused by the Second World War. These issues were still being felt well in to the 1980s with much East and South East London, particularly along the Thames, still bomb sites. The old housing stock of two-up-two-down terraces with outdoor toilets were also woefully out of date. One solution was to build New Towns, a new commuter belt. Another was to build up, communities in the sky with modern homes, heated, indoor plumbing, communal spaces, shops, pubs; everything a family could want or need all within the block.

At its peak over 3,000 people lived in the Heygate, which along with its near neighbour the Aylesbury (current population 7,500), were part of the post-war Utopian dream of transforming urban living spaces through radical design. The brutalist architecture, a style that grew in reaction to pre-WWII art deco and chosen to reflect the more serious world of the Cold War (its pre-fabricated concrete was also cheap for countries still struggling with war debt), came to represent all that was right and wrong with the schemes. Simple, functional design, meant to be useful not pretty, whose good intentions fade in the face of damp British winters that can stain and leech the concrete of character. The social discussion is still ongoing, particularly with regard to the Aylesbury which is currently the subject of ongoing regeneration plans. Similar plans saw the Heygate demolished whilst the larger Aylesbury has been divided into phases, some of which have begun.

It is without doubt that the first residents of both estates welcomed their new homes. Larger than the homes that made up much of London's social housing stock they enjoyed indoor plumbing, heating and large communal spaces including landscape gardens. However, over the years perceived issues with crime and depravation lead to Southwark Council drawing up plans for redevelopment in the 1990s.

Many residents (and their testimonies form the basis of many online history projects such as www.heygatewashome.org) have complained that its bad reputation was due to media representation - both news stories that unduly focussed on crime and the subsequent fictionalised portrayals of urban decay that used the estate as a setting, such as the infamous dystopian Channel 4 ident (you can see a fantastic reaction re-made by local residents online). Locals point to Metropolitan Police figures from the late 1990s that show that the Heygate had a crime rate 40% lower than the Borough of Southwark average and that the council’s own survey from 1998 rated the estate as ‘above average’ for the condition of its housing stock.

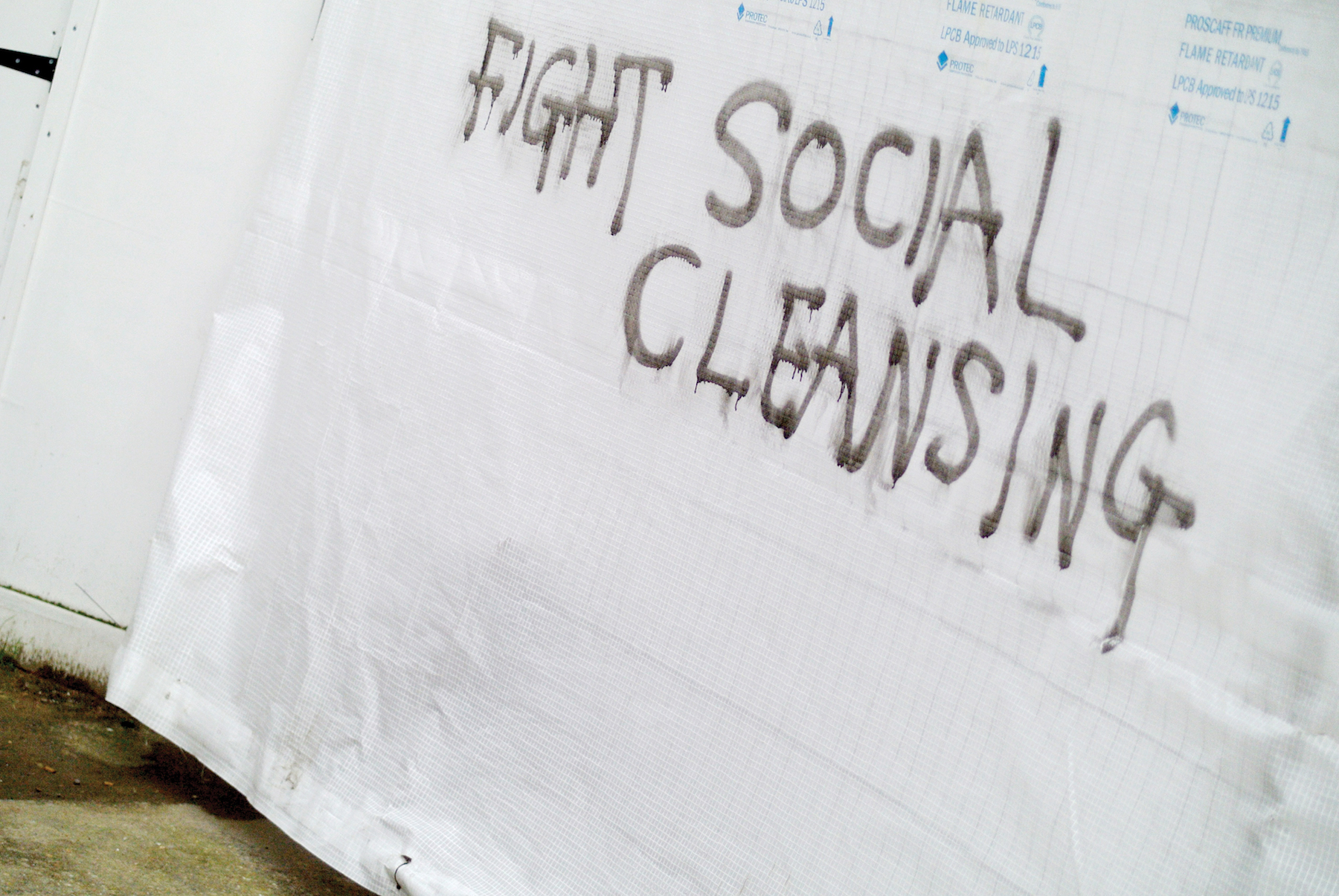

The redevelopment project has been highly criticised by former residents who see it is putting profit above community. The Heygate and Aylesbury are very attractive sites to developers with the space to put high-density housing, retail and commercial units right by major transport links within Zone 1. But the cost to the established community has been huge, with life-long neighbours separated widely across London’s boroughs. Promises of a Right of Return for former residents have been dismissed by resident groups who point to an end date of 2015 for the promise - and the fact that only one, unsuitable phase has been completed as symptomatic of mismanagement and broken promises at every stage. Aylesbury resident groups are making the same arguments as those at the Heygate did – that the estate just needs better investment in what they have, not a big ‘knock-it-down-start-again’ project, particularly one that will not reflect the diversity and community that has been replaced.

The new development will add a new thirty-seven storey tower to South East London’s skyline – One The Elephant - a proposed mix of living, retail and commercial spaces. The council and Lend Lease, the developer behind the scheme, stand by their claims that the estate was (and “is” in the case of the Aylesbury) unsustainable and that the new development will revitalise the area.

The Strata, the Heygate and Aylesbury and The Shard in many ways develop the approach to tower block living.The Heygate and Aylesbury were built solely for social housing use. Over time ‘right to buy’ has mixed in a large proportion of private owners and the increase of housing association management has blurred the lines between state owned housing stock and private rentals. The Strata was built with these developments in mind being designed to accommodate private ownership (including luxurious penthouses) as well as housing association part-ownership, whilst The Shard takes it even further, a glass monument to commerce and transient living where those that can afford to live there often spend very little time there. Communities in the sky are now a private enterprise. All four raise the question, what do we see social housing for? When the Heygate and Aylesbury were built it was for all, for families, for people starting out. Successive government policies seem have shunted it to a position of ‘housing of last resort,’ justifying it as something that needs to be paid for by selling off prime real estate for private housing.

Sharing a similar aesthetic to the Heygate and Aylesbury, Guy's Tower (143 metres) has fared better in the public imagination. Completed in 1974 it was and remains (after some renovation work in 2014) the tallest hospital building in the world. Another brutalist edifice perhaps it's private ownership and status as a hospital has saved it from the opprobrium levelled at its neighbouring 1970s estates. These four edifices, all within the same corner of south east London, represent the modern history of high-rise living, from social experiment to thrusting commerce, as well as the ongoing political and social conversations to do with our ever-changing city.

WORDS: Bobby Diabolus

bobbydiabolus.co.uk

PHOTOS: Jim Eyre

@jimeyrejimeyrejimeyre